Which Formal Approach Dominated Later French Gothic Figural Arts

There are few periods in the Middle Ages in which the vegetal and anthropomorphic forms of architectural ornament exhibit the same diverseness and creative quality as in the later thirteenth century. Capitals and friezes of Gothic churches of this period are full of naturalistic leaves that vividly and seductively suggest the empirical discovery of nature. That this moment of apparent naturalism was far from inevitable is demonstrated by the new stylisation of artistic forms that emerged in nearly all European countries from the beginning of the fourteenth century.[1]

Considering the particular importance of naturalistic ornament in the thirteenth century, studies of the phenomenon are surprisingly rare.[2]This is probably due to potency of geometrical patterns in Gothic architecture in the aforementioned decades in which naturalistic foliage was flowering. This new organisation of the so-calledstyle rayonnant—the virtually famous example being the royal Sainte-Chapelle in Paris—was characterised by technical boldness and past geometrical designs, especially in window tracery, as a consequence of avant-garde planning methods and as an expression of the intellectualisation of architecture.[iii]

Thestyle rayonnant, elaborated in French republic under the reign of King Louis Nine, generated a organization of planning and constructing that became the dominant model for church building throughout Europe. Outside French republic the technological prerequisites for such systematic geometrical planning existed only in a reduced form. In other European countries, we discover that only isolated formal motifs derived from the Rayonnant system were integrated into local edifice traditions. Examples include Westminster Abbey in England; the cathedral of Regensburg and the parish church of St. Marien in Lübeck, both in Frg; and the cathedral of Uppsala in Sweden.[four] In my view, at that place are only two 'pure' examples of Rayonnant architecture outside France: the cathedrals of Cologne in western Germany and of León in northern Spain (Fig. 2.1), of which just the latter was finished in the Centre Ages.

Indeed, the cathedral of León, built from 1255, can be considered an export work of the French Rayonnant style, because its structure does not testify any traces of Castilian traditions. Its outset architect, Main Simon (mentioned in 1261), probably came to Spain together with a team of skilled stonemasons from Champagne. This is confirmed by comparisons with several churches from that region: the programme of León Cathedral recalls that of the cathedral of Reims; the façade shows analogies with Saint-Nicaise at Reims, the inner structure with Saint-Jacques in the same town. The closest similarities are with the cathedral of Châlons-en-Champagne (ca. 1230–1260), and information technology is possible that Master Simon had been trained in its workshop. The builder included, moreover, references to French purple buildings such as Saint-Denis and the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.[5]

In this essay I will focus not on the geometrical systems of thestyle rayonnant, but instead on its rich sculptural decoration and naturalistic forms. Returning to the earliest phases of Gothic architecture, we observe the substitution of the rich compositions of figurative scenes, leaves and ribbons that characterise late Romanesque decorations with standardised vegetal capitals in the grade of buds, so-calledcrochets. Only in the second quarter of the thirteenth century there evolved a more than complex world of naturalistic foliage, including the precise imitation of particular kinds of leaves equally a result of empirical studies of nature. This fascinating new procedure was pioneered at Reims Cathedral (Fig. 2.2), and several churches in Germany, such equally Saint Elisabeth's in Marburg or Naumburg Cathedral (Fig. ii.3), exhibit famous examples of Gothicimitatio naturae.[6] Naturalistic foliage of the same type is found in some English buildings of the early Decorated Way, most famously the affiliate house of Southwell Minster, built in the 1270s.[7]

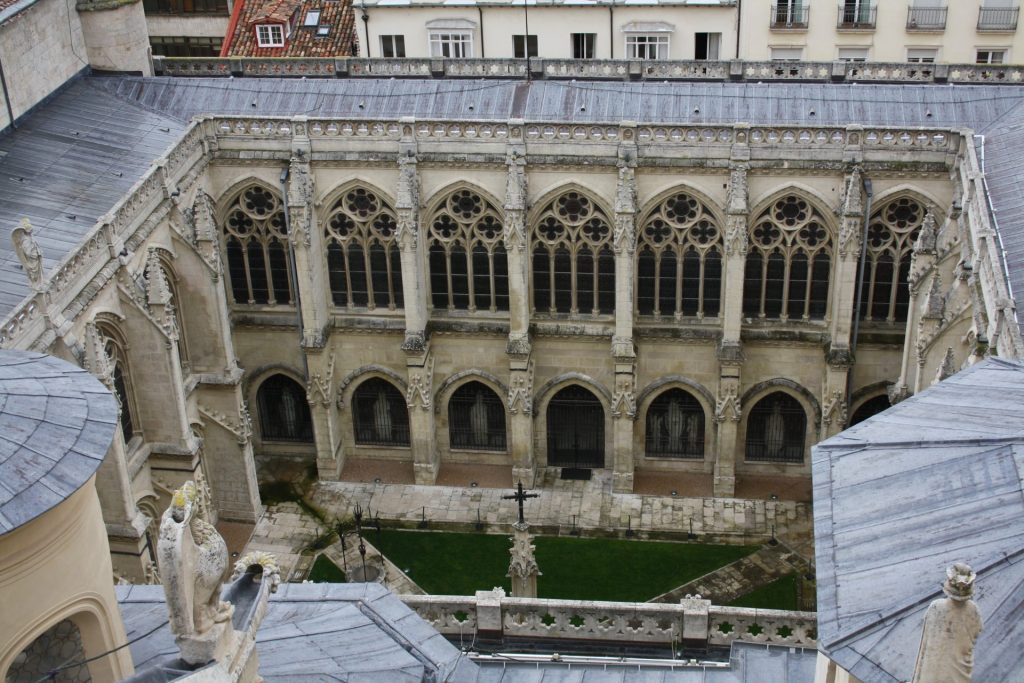

To some extent such exuberant naturalistic leaf sits awkwardly with the refined geometry of Rayonnant buildings, and in most cases such ornamentation was restricted to discrete areas of the church, such every bit portals. If we condone the special cases of Italy and England, where the French Rayonnant system was never adapted completely, there is only one group of buildings that combines rich vegetal ornament with the architectural organisation of thefashion rayonnant.[8] These are the ecclesiastical buildings created in the third quarter of the thirteenth century in the kingdom of Castile, buildings that stand for a specific creative current in the reign of Rex Alfonso the Learned (1252–1284). The most of import examples are the curtilage of the cathedral of Burgos, the presbytery of Toledo Cathedral, some portals in the abbeys of Las Huelgas de Burgos and Cañas (Rioja), and the triforium in the nave of the cathedral of Cuenca. These monuments accept been examined thoroughly past diverse authors, but the lavish decoration of Spanishstyle rayonnant buildings has never been comprehensively studied.

The most important sculptural and ornamental ensemble of this grouping is the cloister, theClaustro Nuevo, of the cathedral of Burgos (Figs. 2.4 to ii.9) – function of a complex programme of extension realised later on the consecration of the cathedral in 1260.[9] The result is one of the well-nigh hit Rayonnant ensembles of anywhere in Europe, and an unusual 1 in view of its high degree of decoration. The architecture of the cloister of Burgos Cathedral corresponds to a groovy extent to the technological and aesthetic system of the Frenchstyle rayonnant, as demonstrated by the similarity of the window tracery (Fig. two.four) to that of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.[10]Vegetal decoration in the Sainte-Chapelle is also quite rich, and on occasion strikingly naturalistic, but in the curtilage at Burgos vegetal decoration has colonised a far greater proportion of the architecture than in other Rayonnant buildings. Leaves of remarkable plasticity not only make full the capitals of the piers but also the arches that reinforce the outer walls of the cloister in two parallel lines (Figs. ii.5 and two.7). Indeed, such is the opulence of the leafage that the geometrical logic of the arches is most hidden. The leaves are elaborated to such a degree that numerous botanical species can exist distinguished. In her important written report of the cloister, the Swiss scholar Regine Abegg identifies vine, ivy, holly and other plants.[11]Various busts, human heads and grotesque figures besides nestle amidst these leaves and in those of the consoles supporting the cloister'south figural sculptures. As these consoles course with the walls of the cloister behind them, it is clear these niggling anthropomorphic figures were executed past the same sculptors responsible for the foliage elsewhere in the cloister.

Most scholars dealing with the Burgos cloister sculptures have focused on the sculpted figures on the outer walls and on the corner piers, some of which are of an extraordinarily high quality. The complex questions of their attribution to unlike artists or workshops cannot be treated here, just I accept suggested elsewhere that they relate to Alfonso the Learned's imperial pretensions. There are several interesting parallels between a number of sculptures in the cloister and western towers of Burgos Cathedral and the famous founders' statues in the cathedrals of Naumburg and Meissen in Germany. I have argued, thus, that the statues of Emperor Otto I the Not bad and his married woman Adelheid in the cathedral of Meissen, dating from the 1250s, served every bit relatively precise models for the commemorative sculptures of Rex Ferdinand 3 of Castile and his married woman Beatrice of Hohenstaufen in the curtilage at Burgos (Fig. ii.6). The latter's hymeneals in 1219 in Burgos' quondam Romanesque cathedral underpinned the imperial pretensions of their son, Alfonso X the Learned, who was elected Roman (German) king in Frankfurt in 1257. In the catamenia of German language-Castilian interchange that followed, a workshop of German sculptors must take been employed in Burgos Cathedral.[12] The artistic connectedness between Saxony and Castile has recently been supported by the observation that several masons' marks on the wall behind the statues of Ferdinand and Beatrice at Burgos are identical to those in the choir of Meissen Cathedral.[thirteen]

Permit us plow now to the decorative sculpture of the curtilage at Burgos. Regine Abegg has already observed that those areas with the highest-quality figural sculpture, especially in the western wall of the curtilage, are decorated with the coarsest and most repetitive vegetal ornamentation (Figs. 2.6 and 2.7). In contrast, very rich and finely elaborated and differentiated foliage tin can be found in the cloister'due south southeast corner and parts of the n walk, precisely those areas that are most afar from the cloister entrance, and where the figure sculpture is of lower quality and significance (Figs. 2.eight and 2.9).[xiv] One of import conclusion tin be derived from this at starting time sight paradoxical observation: ii different workshops worked independently, one responsible for the foliate decoration and small decorative figures, and some other for the figure sculpture.[15] They may have worked simultaneously, but according to their own plans and rhythms.

In the cloister of Burgos Cathedral two dissimilar teams must so have been active, both directed past Main Enricus equally themagister operis of the whole structure: on the 1 hand, the figure sculptors, divided into different teams and specialised in the artistic representation of human figures on a monumental scale; on the other, the decorative sculptors, likewise split into teams responsible for the ornamentation of capitals, consoles and arches. This latter grouping can be classified, as we will meet, equally a specialised branch of stonemasons that created in the cloister of Burgos Cathedral a whole microcosm of plants and little figures, often of a grotesque grapheme.

It is difficult to prove this ramification of professions through documents.[16] All those who worked in stone—and not wood, the work of the carpenters—belonged to the branch of masons (pedrerosin Castilian) regardless of their particular part, and oft received the same salary.[17] In that location are cases in which stonemasons who worked on highly ornamented pieces were better paid, only it does not seem to have been a general rule.[18]Clear evidence for this is provided by theLivre des métiers, written past Etienne Boileau around 1268, exactly the period under discussion.[nineteen] In this statute of the crafts and trades of Paris, we find a distinction between the professions ofimagiers-sculpteurs on the ane hand andtailleurs d'images on the other.[20]This seems to correspond to the difference between figural and decorative sculptors.

The famous lower scenes of the Saint-Chéron window in the cracking northern chapel of the ambulatory of Chartres Cathedral are very instructive.[21] They prove bricklayers, stonemasons and sculptors. The activities of a stonemason, who controls the regularity of a wall with a plumb line, and of three stonemasons, who carve unproblematic and profiled ashlars, are gathered in the left scene, while the right is reserved for the sculptors of tall reliefs of kings. Stonemasons and sculptors are non distinguished by their dress, simply the correct scene gives a more relaxed impression considering one sculptor is treating himself to a drinking glass of water or wine, perhaps an indication of the higher social rank of his artistic profession. In whatever example, the scenes testify a clear distinction between the piece of work of stonemasons and sculptors. So in which category did the sculptor of decorative pieces, such as capitals, belong? A stained glass image in the Lady chapel of Saint-Germer-de-Wing (Fig. 2.10), a masterwork of Rayonnant architecture erected between 1259 and 1267 (and thus contemporaneous with the cloister of Burgos), is very instructive in this respect every bit it implies that uppercase carving was i of the activities of stonemasons.[22]This is one more indication that the artisans who created the leafage and miniature figures at Burgos were classified as stonemasons, and should be distinguished from figure sculptors.

A history of ornamental or decorative sculpture, in which sculptors had considerable artistic freedom but not the particular skills required for effigy sculpture, has all the same to be written. Like sure other artistic genres, such as wooden reliefs in choir stalls or manuscript marginalia, ornamental sculpture offered a infinite where artists could experiment inventively with different subjects and iconography. Thus, non only can busts of angels exist found on the pilasters of the curtilage of Burgos, just besides numerous head sculptures as well as animals and monsters, which are at least partially conceivable as genre representations or grotesques. The decorative sculpture of the cloister determines the overall impression to such an extent that the technological character and geometric aesthetics of the Rayonnant architecture have been considerably reduced. On the other hand, as the space most closely associated with thecabildo, the cathedral chapter, the curtilage enjoys a splendour which is not found in comparable buildings in France.

Having recognised the autonomy of the workshop responsible for the decorative sculpture in Burgos Cathedral's cloister, it seems logical that the aforementioned workshop was agile in some other building project that was underway at around the same time on the outskirts of Burgos: the completion of the royal abbey church building of Las Huelgas. Every bit I have demonstrated elsewhere, the church building of this royal Cistercian nunnery was erected hurriedly in the first 2 decades of the thirteenth century, making it the first High Gothic building in Castile. The nave of the church was left semi-finished, however, with unfinished piers, uncarved capitals and no vaults (Fig. ii.11). The ribbed vaults of the nave were added in the 2d half of the thirteenth century, old earlier the documented consecration of the church in 1279, and probably in the context of the burial of the infante Fernando de la Cerda, who died in 1275.[23]Also every bit the tomb of Fernando de la Cerda in the north alley, a new main portal was constructed in the northern transept façade around the time of the consecration of 1279. Iii portals in the main cloister (now known as the cloister of San Fernando) that lead into the southward aisle and sacristy, were built a footling earlier, probably around 1270 (Fig. two.12), and show shut parallels with the cathedral cloister.[24]For example, segmented arches—unusual in French Rayonnant compages—are employed both in these portals and in the entrance to the cathedral cloister. The very dense and naturalistic foliage that covers the archivolts and tympana of the abbey portals was certainly made by members of the decorative workshop active in the cathedral cloister.[25]

The naturalistic leaf of the 2 Burgos cloisters is developed further at the Cistercian convent in Cañas (Rioja), synthetic in the concluding decades of the thirteenth century with forms that derive directly from Parisian Rayonnant architecture (Fig. ii.xiii). Raquel Alonso has noted that the vegetal decoration of the archway portal of the chapter house at Cañas (Fig. 2.xiv) closely recalls the foliage of the Las Huelgas portals.[26] They cannot, however, have been carved by the aforementioned workshop: the leaves of the Cañas portal lack the plasticity and density of the foliage of the cloisters of Burgos Cathedral and Las Huelgas; instead each leaf is more clearly isolated and stylised—role of a wider tendency in several European countries at the end of the thirteenth century.[27]

As mentioned above, the cathedral of León is an exception within thirteenth-century Castilian architecture insofar as its constructional system is fully in line with the Frenchstyle rayonnant as it was adopted in the churches of the Champagne region. This means that the formulation of the walls, pillars and windows in León is shaped by clear geometrical forms and does non even come shut to the decorative richness of the cloister of Burgos. In contrast, the portals of León Cathedral, which are equipped with elaborate sculptural programmes, have an abundant vegetable and heraldic ornamentation. Information technology is no coincidence that these portal complexes, which are hardly connected to the cathedral's core structure, all refer to the model of Burgos Cathedral: the primal southern portal is near a copy of the Puerta del Sarmental, and the central northern one of the Burgos curtilage portal.[28] In all likelihood, this connection can exist traced back to Principal Enricus, documented in his twelvemonth of decease in 1277 as themagister operis of both the cathedral of Burgos, where his family lived, and that of León.[29]

The most interesting example of lavish decorative sculpture with a clear relationship to the cloister of Burgos Cathedral is the triforium of the cathedral of Cuenca, at the southeastern border of the kingdom of Castile—a considerable distance from the one-time Castilian majuscule.[30] Work at that place was interrupted following the construction of the choir and transepts in the first quarter of the thirteenth century, so that the ii-storey nave was erected but in the 2d half of the century (Figs. ii.15 and 2.16). Diverse parts of the cathedral, such as the circular windows in the aisles, refer to the model of the abbey church of Las Huelgas and ultimately to Gothic buildings in the Parisian region, such as the church of Arcueil.[31] Most interesting is the nave triforium, which incorporates the clerestory windows. Here a particular tracery grade was employed that consists of an oculus set over two trilobed arches. Sculptures of angels are fastened to the mullions (Figs. 2.xvi and 2.17).[32] The inclusion of awe-inspiring sculpture in the combined triforium and clerestory zone is unique in Gothic architecture: an extremely ambitious solution, it was probably realised nether Bishop Pedro Lorenzo, who governed the diocese of Cuenca between 1261 and 1272 and was a close confidant of King Alfonso the Learned.[33]

The combination of tracery and statues in Cuenca's triforium recalls the galleries over the façades of Burgos Cathedral, especially that over the due south transept, with statues of angels that ultimately derive from those at Reims and Saint-Denis.[34] The ornamental richness at Cuenca is comparable to the cloister of Burgos, but the elaboration of details differs somewhat and must be the responsibility of a dissimilar workshop. In the triforium of Cuenca the middle is caught past lines of rather curious elements, similar rolled upwards leaves or snail shells, sometimes ending in miniscule grotesque heads. The trilobed arches are prepare with rows of buds, clearly imitating the crockets used widely in thirteenth-century compages in French republic. The numerous ornamental heads at Cuenca resist iconographic interpretation and tin can maybe be best understood in terms of the grotesque. Like lines of ornamental heads had been used in the triforium of the cathedral of Burgos from virtually 1230 onwards, and they appear again in the presbytery triforium of Toledo Cathedral in the 1250s (Fig. 2.19).[35]

The most interesting feature of the architectural and decorative organisation of Cuenca Cathedral is the combination of tall sculptures of angels with the ornamental sculpture that well-nigh entirely covers the fragile Rayonnant architecture. In this instance, I would suggest that in that location was no separation between ornamental and figural sculptors. In contrast to the angels in the transept gallery and the kings and bishops in the cloister of Burgos Cathedral, the angels of Cuenca do not appear monumental, despite their size. Their members are not worked out organically, nor do they generate the impression of corporeality. Comparisons between the heads of the statues of angels and the small decorative heads around them demonstrate clearly that all these figures were made by the same workshop. In this special case, a workshop of decorative sculptors, accustomed to producing leaves and isolated heads, had to create complete sculptures of monumental size, and the result is non entirely convincing.

If we regard the miracle of a highly decorated Rayonnant architecture in Castile from a wider perspective, we can also take into account the Islamicate decorations of Toledo Cathedral.[36] In the ambulatory triforium, decorative motifs referring to Andalusi mosques and/or the earlier mosque-cathedral of Toledo were already installed in the second quarter of the thirteenth century. The most striking references to Islamic traditions were, however, created subsequently the eye of the century, under King Alfonso 10.[37]These include the circuitous triforium decoration in the presbytery and the subtle plasterwork decoration of the tomb of thealcalde Fernán Gudiel (d. 1278), in the chapel of San Pedro on the due south side of the nave (Figs 2.18–two.twenty).[38]The Arabic-style decorations include circuitous geometrical patterns that are fundamentally different from the structural logic of thestyle rayonnant, and in Toledo'due south presbytery they were incorporated inside the Rayonnant organization then that they announced like images of a strange aesthetic culture exhibited within a modern architectural frame that was shaped by French models. The combination of both systems produced a level of artistic splendour that trumped whatsoever cathedral in Kingdom of spain or France.

In his monograph on Toledo Cathedral, Tom Nickson developed the convincing thesis that the star-shaped vaults of the presbytery, mostly considered as an addition of the late fifteenth century, were in fact built in the early on 1270s as the last function of the cathedral chevet. Indeed, the profiles and decoration of the ribs friction match the ornament of the presbytery walls, and the Y-shaped triradials of the loftier vaults, which include not only tiercerons but also liernes, are a logical continuation of the vault system of the two ambulatories, where tripartite and quadripartite vaults alternate regularly (Fig. 2.21). This means that it was in Toledo—and not in England—that Europe's beginning lierne vaults were developed and built.[39] What is more, the star patterns that result in the 2 presbytery vaults effectively crown the uniquely complex architectural system of the chevet, and increase its highly decorated appearance, transforming architectural structure into paradigm and surpassing in richness all other cathedrals in France and Spain. The presbytery of Toledo Cathedral thus belongs to a group of of import and lavishly decorated church buildings in Castile that to some sure extent transformed the system of thefashion rayonnant adapted from French models. Geometrical purity was sacrificed for the sake of decorative splendour, which was surely regarded every bit a sign of the special dignity of the churches, and as an expression of magnificence. Ane could call it a 'sumptuous style', consistent with the terms of the papal indulgence issued in 1223 to allow Burgos Cathedral to rise 'nobly and indeed sumptuously'.[40]

It is no coincidence that this sumptuous style of compages and decoration is characteristic of some of the nigh important cathedrals in Castile, or parts of them, built in the reign of Alfonso the Learned (1252–1284) (Fig. 2.22). The Castilian bishops, decisive promoters of cathedral construction, were dependent on the royal court to a college degree than in other countries of Europe. They passed considerable parts of the twelvemonth in Alfonso'south court instead of their dioceses. Indeed, the two archbishops of Toledo who were responsible for the spectacular completion of the cathedral chevet, Sancho I of Castile (1251–1261) and Sancho II of Aragon (1262/66–1275), were even members of the purple family.[41] Above all, Cuenca seems to accept been a staging post for ambitious clerics at the royal court. Pedro Lorenzo, former archdeacon of Cádiz, was bishop of Cuenca between 1261 and 1272—the period in which the lavish triforium of the cathedral was synthetic—and at the same time was recognised every bit 'the male monarch's closest collaborator'.[42]Several of his predecessors and successors left the come across of Cuenca to go along their careers, often in Burgos, and occasionally fifty-fifty made it to the archbishopric of Toledo. This was the case of Gonzalo Pérez ('Gudiel'), an of import collaborator in the literary enterprises of Alfonso the Learned. Having served as the male monarch's notary betwixt 1270 and 1272, Gudiel became bishop of Cuenca in 1273 and of Burgos in 1275; at the cease of his career, between 1280 and 1299, he was archbishop of Toledo, becoming one of its virtually of import archbishops in the Gothic period.[43]

It should besides be mentioned that Alfonso Ten enjoyed a close relationship with Martín Fernández, who, every bit bishop of León between 1254 and 1289, oversaw construction of a cathedral distinguished not by sumptuous architectural decorations but by very close adaptations of French Rayonnant models.[44] In 1263, the king fifty-fifty sent the Leonese bishop to the papal curia in Rome to defend his imperial pretensions, but, having been forced into exile at the end of Alfonso'due south reign, Fernández turned against the male monarch.[45] On the other manus, Bishop Fernando de Covarrubias of Burgos (r. 1280–1299) remained a loyal supporter of Alfonso right up until his death in 1284.[46]

The purple court was manifestly a place where ecclesiastical careers were planned and probably where projects of representation, such every bit the construction and ornament of cathedrals, were discussed. This does not hateful that the sumptuous decorative style of Castilian churches was centrally planned in the courtroom of Alfonso the Learned, but information technology must be assumed that the strikingly decorative qualities of these cathedrals and of the imperial abbey of Las Huelgas stem at least partly from a climate of cooperation and competition at the royal court.

Alfonso'due south court was, after all, the court of the elected king of Federal republic of germany, which is to say the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, the highest secular dignity in the Christian world. It is true that Alfonso'south expensive and futile efforts to attain recognition every bit emperor by the papal court and the electors of Federal republic of germany ultimately price him the support of the Castilian nobility and several previously faithful bishops.[47] But the reorganisation of the royal court that followed Alfonso'southward ballot did include the establishment of a special imperial notary, staffed with officials from Italy and separate from the royal notary.[48] In this sense, the architectural splendour and lavish ornament of Spanish churches under prelates in the ladylike circle (namely the cathedrals of Toledo and Cuenca) or those close to the king (Burgos Cathedral and Las Huelgas) may exist understood as an attempt to projection a particularly high level of creative formation, as appropriate to the representation of the Roman emperor.[49]

Some of these buildings were patently intended to impress purple guests from abroad: Burgos was the favourite place for imperial weddings, which occurred either in the cathedral, where the new cloister was the perfect identify to commemorate the conjugal connection between Alfonso's father and Beatrice of Hohenstaufen, or in the majestic monastery of Las Huelgas. Of particular importance were the wedding of the English heir, Edward, with Alfonso'southward sister, Eleanor, in 1254, and the marriage of Alfonso'south son and heir, Fernando de la Cerda, with Blanche, the daughter of the French rex Louis Ix, in 1269. The latter was celebrated precisely fifty years after the Hohenstaufen wedding in the old cathedral of Burgos on which the imperial pretentions of Alfonso 10 were founded.[fifty] We should not underestimate the importance of ecclesiastical buildings in the staging of such regal ceremonies, and this political importance obviously called for a high degree of decoration that surpassed the geometrical purity of thefashion rayonnant.

Citations

[ane] Roland Recht, 'Le goût de 50'ornement vers 1300', in Danielle Gaborit-Chopin and François Avril (eds.), 1300…: L'art au temps de Philippe le Bel. Actes du colloque international, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, 24 et 25 juin 1998 (Paris: Ecole du Louvre, 2001), pp. 149-161.

[ii] Run into, nonetheless, the classic study past Nikolaus Pevsner, The Leaves of Southwell (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1945). Mailan Southward. Doquang, The Lithic Garden: Nature and the Transformation of the Medieval Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018) was published as this essay came to printing.

[3] Major works of synthesis on the style rayonnant are still defective. Two key studies are Robert Branner, St Louis and the Court Style in Gothic Architecture (London: Zwemmer, 1965); and Dieter Kimpel and Robert Suckale, Die gotische Architektur in Frankreich 1130-1270 (Munich: Hirmer, 1985), pp. 334-469. The dominance of geometric designs, extended to all genres of microarchitecture such every bit retables and reliquaries, continued to increase in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. See Christine Kratzke and Uwe Albrecht (eds.), Mikroarchitektur im Mittelalter: ein gattungsübergreifendes Phänomen zwischen Realität und Imagination (Leipzig: Kratzke, 2008), esp. Peter Kurmann, 'Mikroarchitektur im 13. Jahrhundert', pp. 83-97.

[4] Virtually recently, Christopher Wilson, 'La cathédrale de Reims et l'abbatiale de Westminster', in Patrick Demouy (ed.), La cathédrale de Reims (Paris: Presses de l'université Paris-Sorbonne, 2017), pp. 273-286.

[5] Recent studies include Manuel Valdés Fernández (ed.), Una historia arquitectónica de la catedral de León (León: Santiago García, 1994); Henrik Karge, '"León en sutileza". La arquitectura medieval de la catedral de León', in Carlos Estepa Díez et al., La Catedral de León. Mil años de historia (León: Edilesa, 2002), pp. 49-87; Joaquín Yarza Luaces, María Victoria Herráez Ortega and Gerardo Boto Varela (eds.), Congreso Internacional "La Catedral de León en la Edad Media" (León: Universidad de León, 2004), esp. Henrik Karge, 'La arquitectura de la catedral de León en el contexto del gótico europeo', pp. 113-144, and María Victoria Herráez Ortega, 'La construcción del templo gótico', pp. 145-176. See, in full general, Henrik Karge, 'De Santiago de Compostela a León: modelos de innovación en la arquitectura medieval española. Un intento historiográfico más allá de los conceptos de estilo', Anales de Historia del Arte, volumen extraordinario (2009), pp. 165-196.

[half dozen] Encounter diverse manufactures in Hartmut Krohm and Holger Kunde (eds.), Der Naumburger Meister – Bildhauer und Architekt im Europa der Kathedralen, iii vols. (Petersberg: Imhof, 2011-2012), published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title at Naumburg Cathedral, Schlöschen and Stadtmuseum Hohe Lilie, 29 June 2011-2 November 2011. In item, meet Elisabeth Harting, 'Der Stil der Naumburger Pflanzenwelt aus botanischer Sicht', 1: pp. 267-280; Lukas Huppertz, 'Voraussetzungen der Ornamentik des Naumburger Meisters', 1: pp. 294-300; Guido Siebert, '"Aeternitas est interminabilis vitae tota simul et perfecta possessio." Sinnbildung und Naturstudium im Pflanzendekor des Rayonnant', ane: pp. 301-309. The classic work is past Lottlisa Behling, Die Pflanzenwelt der mittelalterlichen Kathedralen (Cologne/Graz: Böhlau, 1964), pp. 64-82 (for Reims) and pp. 90-112 (for Naumburg).

[7] Meet Nicola Coldstream, The Decorated Style. Compages and Ornament 1240–1360 (London: British Museum Press, 1994), p. 33; Philip Dixon and Helene Seewald, '"The Leaves of Southwell." Höhepunkte englischer Laubwerkornamentik', in Krohm and Kunde, Naumburger Meister, i: pp. 281-293 (compare notation 2).

[8] The famous examples of exuberant decoration in the English Decorated churches are only superficially comparable to the Spanish examples studied in this essay. Come across Jean Bony, The English Decorated Way. Gothic Architecture Transformed 1250-1350 (Oxford: Phaidon, 1979), pp. 19-29; Coldstream, Decorated Way; Paul Binski, Becket's Crown: Art and Imagination in Gothic England, 1170-1300 (New Haven: Yale Academy Printing, 2004), pp. 90-99; Peter Draper, The Germination of English Gothic. Architecture and Identity (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2006), pp. 244-249.

[9] See my earlier studies of Burgos Cathedral and Regine Abegg'southward monograph on the cloister: Henrik Karge, Die Kathedrale von Burgos und die spanische Architektur des xiii. Jahrhunderts. Französische Hochgotik in Kastilien und León (Berlin Gebr. Isle of man, 1989), pp. 77, 177-180; La Catedral de Burgos y la Arquitectura del siglo XIII en Francia y España (Valladolid: Junta de Castilla y León. Consejería de Cultura y Turismo, 1995), esp. pp. 109-110, 256-262; 'La arquitectura gótica del siglo 13', in Luis García Ballester (ed.), Historia de la Ciencia y de la Técnica en la Corona de Castilla, vol. one: Edad Media (Valladolid: Junta de Castilla y León. Consejería de Educación y Cultura, 2002), pp. 543-599, esp. pp. 555-559 and 593-595. Also see Regine Abegg, Königs- und Bischofsmonumente. Die Skulpturen des 13. Jahrhunderts im Kreuzgang der Kathedrale von Burgos (Zurich: InterPublishers, 1999). For a recent study, see Henrik Karge, 'Les programmes sculpturaux des cathédrales de Reims et Burgos et leurs références royales', in Patrick Demouy (ed.), La cathédrale de Reims (Paris: Presses de l'université Paris-Sorbonne, 2017), pp. 287-310. On the restoration of the Claustro Nuevo at the turn of the twentieth century, see Eduardo Carrero Santamaría, 'Restauración monumental y opinión pública. Vicente Lampérez en los claustros de la catedral de Burgos', Locus Amoenus 3 (1997): pp. 161-176, esp. pp. 163-169.

[10] Run across Karge, Catedral de Burgos, p. 182.

[11] See Abegg, Königs- und Bischofsmonumente, pp. lx, 78-79.

[12] See Henrik Karge, 'From Naumburg to Burgos. European Sculpture and Dynastic Politcs in the Thirteenth Century', in Hispanic Research Journal xiii (2012): pp. 432-446; Henrik Karge, 'Meissen – Constance – Burgos. European Sculpture and Dynastic Politics in the Thirteenth Century', in Hartmut Krohm and Holger Kunde (eds.), Der Naumburger Meister – Bildhauer und Architekt im Europa der Kathedralen (Petersberg: Imhof, 2012), 3: pp. 242-252; Karge, 'Reims et Burgos, références royales', esp. pp. 305-310.

[13] The inquiry was undertaken in 2013 by Günter Donath, architect of Meissen Cathedral, his wife Maria Donath and the author of this essay. See Günter Donath, 'Zog die Naumburger Werkstatt von Meißen nach Burgos? Eine bauarchäologische Spurensuche im Kreuzgang der Kathedrale von Burgos', in In situ. Zeitschrift für Architekturgeschichte half-dozen (2014): pp. 39-52; Karge, 'Reims et Burgos, références royales', pp. 305-308.

[xiv] Abegg, Königs- und Bischofsmonumente, pp. lx-62.

[fifteen] Abegg, Königs- und Bischofsmonumente, p. 62, reaches a like conclusion.

[16] At that place are some cases in which there is a differentiation between lathomi and artifices but no definition of the term artifex, for case in the Vita Sugerii, abbatis Sancti Dionysii written by the monk Guillaume. See Victor Mortet and Paul Deschamps, Recueil de textes relatifs à l'histoire de l'architecture et à la status des architectes en French republic, au Moyen Âge (XIIe-XIIIe siècles) (Paris: Picard, 1929), pp. 86-88, esp. p. 87.

[17] The full general division of architectural practise into the branches of carpenters and masons is already constitute in the nomenclature of the artes mechanicae past Hugo of St. Victor: Hugonis de S. Victore Didascalion de studio legendi, Volume Two, ch. XXIII (Patrologia latina, éd. Migne, vol. CLXXVI, col. 760-761; Mortet and Deschamps, Recueil de textes, pp. 21-22).

[18] This is documented in the Cloth Accounts of Prague Cathedral. See Pierre du Colombier, Les chantiers des cathédrales. Ouvriers – architectes – sculpteurs, rev. ed. (Paris: Picard, 1973), p. 117. See also Joan Domenge i Mesquida, 'Le portail du mirador de la cathédrale de Majorque: du document au monument', in Bernardi, Hartmann-Virnich and Vingtain (eds.), Texte et archéologie monumentale: approches de 50'architecture médiévale (Montagnac: 1000. Mergoil, 2005), pp. x-26, esp. p. 12.

[19] René de Lespinasse and François Bonnardot (eds.), Le 'Livre des Métiers' d'Etienne Boileau, Histoire générale de Paris, Collection de documents (Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1879).

[20] Come across Colombier, Chantiers des cathédrales, pp. 136-137. For later examples of this stardom, see Joan Domenge i Mesquida, 'Guillem Morey a la seu de Girona (1375-1397). Seguiment documental', Lambard nine (1996): pp. 105-31, esp. p. 109.

[21] For a summary of current inquiry, see Brigitte Kurmann-Schwarz and Peter Kurmann, Chartres. Die Kathedrale (Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 2001), esp. pp. 133-136, 180, and Plate 71. See likewise Günther Binding and Norbert Nußbaum, Der mittelalterliche Baubetrieb nördlich der Alpen in zeitgenössischen Darstellungen (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1978), pp. 154-155, and, Figs. 87 and 88.

[22] Binding and Nußbaum, Der mittelalterliche Baubetrieb, pp. 166-167, Fig. 99; Kimpel and Suckale, Gotische Architektur in Frankreich, pp. 428-431, esp. p. 429 and Plate 445.

[23] Henrik Karge, 'Die königliche Zisterzienserinnenabtei Las Huelgas de Burgos und dice Anfänge der gotischen Architektur in Spanien', in Christian Freigang (ed.), Gotische Architektur in Spanien. La arquitectura gótica en España, Ars Iberica (Frankfurt am Main and Madrid: Iberoamericana Vervuert, 1999), pp. 195-222; 'La arquitectura gótica del siglo Xiii', in Luis García Ballester (ed.), Historia de la Ciencia y de la Técnica en la Corona de Castilla, vol. 1, Edad Media (Valladolid: Junta de Castilla y León 2002), pp. 543-599, esp. pp. 543-549. In these studies, I proposed that the beginning of the structure of the abbey church building should be dated around 1200, on the basis of some key documents from 1203, and that this signified a radical predating of the church edifice in comparison to the traditional stance of a construction around 1220 (cf. Torres Balbás, Lambert and others). In the concurrently, James D'Emilio and Pablo Abella Villar accept argued for an even earlier beginning, probably in the 1190s. See James D'Emilio, 'The Purple Convent of Las Huelgas: Dynastic Politics, Religious Reform and Artistic Change in Medieval Castile', Studies in Cistercian Art and Architecture 6 (2005): pp. 191-282; Pablo Abella Villar, Patronazgo regio castellano y vida monástica femenina: morfogénesis arquitectónica y organización funcional del monasterio cisterciense de Santa María la Existent de Las Huelgas de Burgos (ca. 1187-1350), 2 vols. (PhD diss., Universitat de Girona, 2015, dig. publ. 2016), esp. ane: pp. 702-745. See likewise Rocío Sánchez Ameijeiras, 'La memoria de united nations rey victorioso: Los sepulcros de Alfonso Eight y la Fiesta del Triunfo de la Santa Cruz', in Barbara Borngässer, Henrik Karge and Bruno Klein (eds.), Grabkunst und Sepulkralkultur in Spanien und Portugal. Arte funerario y cultura sepulcral en España y Portugal (Frankfurt am Main and Madrid: Iberoamericana Vervuert, 2006), pp. 289-315; Gema Palomo Fernández and Juan Carlos Ruiz Souza, 'Nuevas hipótesis sobre Las Huelgas de Burgos. Escenografía funeraria de Alfonso Ten para un proyecto inacabado de Alfonso 8 y Leonor Plantagenêt', Goya 316-317 (2007): pp. 21-44.

[24] See Abella Villar, Patronazgo regio castellano, 1: pp. 520-527.

[25] Come across Abegg, Königs- und Bischofsmonumente, pp. 81-82. The ornaments of the tomb of Fernando de la Cerda and the northern portal of Las Huelgas evidence a slightly more than developed mode of vegetable decoration.

[26] Raquel Alonso Álvarez, El monasterio cisterciense de Santa María de Cañas (La Rioja). Arquitectura gótica, patrocinio aristocrático y protección real (Logroño: Gobierno de La Rioja. Instituto de Estudios Riojanos, 2004), esp. pp. 100-102.

[27] The regal monastery of Santa María la Real de Nieva nearly Segovia, erected in the showtime one-half of the fifteenth century, shows how far the tendency of simplification of sculptural decorations could lead. See Diana Lucía Gómez-Chacón, El Monasterio de Santa María la Existent de Nieva. Reinas y Predicadores en tiempos de reforma (1392-1445) (Segovia: Diputación de Segovia, 2016).

[28] See Ángela Franco Mata, Escultura gótica en León y provincial (1230-1530) (León: Instituto Leonés de Cultura 1998), pp. 51-357; and 'Escultura medieval. Un pueblo de piedra para la Jerusalén Celeste', in Carlos Estepa Díez et al., La Catedral de León, esp. pp. 94-135. Near the connections to Burgos, see Karge, Catedral de Burgos, pp. 187-193. Various tombs of clerics in the cloister of León which were created effectually 1260 likewise prove rich vegetable ornamentation. See Franco Mata, Escultura gótica en León, pp. 401-412, and 'Escultura medieval', pp. 137-143.

[29] The obituaries of both cathedrals record the same day of death, 10 July 1277. The indication in León runs equally follows: 'Half dozen. idus julii. Eodem die sub era MCCCXV obit Enricus magister operis.' Archivo de la Catedral de León, Obituario, fol. 97r. Note the spelling of the name Enricus without the initial H. Run across Karge, Catedral de Burgos, pp. 193-195.

[thirty] Encounter the fundamental monograph on this: Gema Palomo Fernández, La Catedral de Cuenca en el Contexto de las Grandes Canterías Catedralicias Castellanas en la Baja Edad Media, 2 vols. (Cuenca: Diputación Provinicial de Cuenca, 2002); and 'La catedral de Cuenca (siglos XII-15)', in Pedro Miguel Ibáñez Martínez (ed.), Cuenca, mil años de arte (Cuenca: Asociación de Amigos del Archivo Histórico Provincial de Cuenca, 1999), pp. 115-186.

[31] See Karge, Catedral de Burgos, p. 184, plates 187-189; Palomo Fernández, Catedral de Cuenca, 1: pp. 244-245.

[32] For an architectural, sculptural and ornamental assay of the triforium in Cuenca, see Palomo Fernández, Catedral de Cuenca, 1: pp. 239-249, and the plates on pp. 417-431.

[33] Various documents testify the close relationship betwixt the king and the bishop of Cuenca. See Palomo Fernández, Catedral de Cuenca, 1: pp. 153-155. The fact that bishop Pedro Lorenzo donated various personal goods at the finish of his life for the construction of an altar frontal in his cathedral indicates that the architectural piece of work of the nave including the triforium was completed before his death in 1272. See Palomo Fernández, Catedral de Cuenca, 1: pp. 154-155.

[34] Encounter Karge, Catedral de Burgos, pp. 184, 223; Karge, 'Reims et Burgos, références royales', p.302.

[35] See Karge, Catedral de Burgos, pp. 175-177 (and p. 152 for models in the Loire region); Tom Nickson, Toledo Cathedral. Building Histories in Medieval Castile (Academy Park: The Pennsylvania State Academy Printing, 2015), p. 84, Figs. 43 and 47.

[36] See Nickson's fundamental piece of work, Toledo Cathedral, pp. 76-94.

[37] See Henrik Karge, 'Die Kathedrale von Toledo oder die Aufhebung der islamischen Tradition', Kritische Berichte 20 (1992): pp. sixteen-28.

[38] See Nickson, Toledo Cathedral, pp. 88-91, 116-120.

[39] Nickson, Toledo Cathedral, pp. 92-94.

[40] Luciano Serrano, Don Mauricio, Obispo de Burgos y fundador de su catedral (Madrid: Instituto de

Valencia de Don Juan, 1922), p. 65.

[41] See Ramón Gonzálvez Ruiz, Hombres y libros de Toledo (1086-1300) Monumenta ecclesiae toletanae historica (Madrid: Fundación Ramón Areces, 1997), pp. 231-295; Francisco J. Hernández and Peter Linehan, The Mozarabic Cardinal: The Life and Times of Gonzalo Pérez Gudiel (Florence: Sismel, Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2004), pp. 75-82, 115-126.

[42] Run across note 33.

[43] Run into the important monograph by Hernández and Linehan, The Mozarabic Cardinal. As well see Gonzálvez Ruiz, Hombres y libros de Toledo, pp. 297-549, and Nickson, Toledo Cathedral, pp. 98-100. The epithet 'Gudiel' was not documented earlier the sixteenth century, simply it has adult a particular historiographic tradition.

[44] Come across Juan Manuel Nieto Soria, 'Los obispos y la catedral de León en el contexto de las relaciones monarquía-Iglesia, de Fernando Iii a Alfonso XI', in Yarza Luaces , Herráez Ortega and Boto Varela, Catedral de León, pp. 99-111, esp. p. 102; Karge, 'Arquitectura de la catedral de León', pp. 124-128; Gregoria Cavero Domínguez, Martín Fernández, un obispo leonés del siglo XIII. Poder y gobierno (Madrid: Ediciones de La Ergástula, 2018).

[45] Karge, 'Arquitectura de la catedral de León', p. 125; Joseph F. O'Callaghan, 'Alfonso X and the Castilian Church', Idea. A Review of Culture and Idea 60 (1985): pp. 417-429, esp. p. 428.

[46] O'Callaghan, 'Alfonso Ten and the Castilian Church building', pp. 426-427. See, in full general, José Manuel Nieto Soria, Iglesia y poder real en Castilla. El episcopado, 1250-1350 (Madrid: Universidad Complutense, 1988).

[47] There is an abundant bibliography about the so-chosen fecho del imperio. See two recent publications from a German and a Castilian perspective: Bruno Berthold Meyer, Kastilien, die Staufer und das Imperium. Ein Jahrhundert politischer Kontakte im Zeichen des Kaisertums, Historische Studien (Husum: Matthiesen, 2002), esp. pp. 113-182; Carlos Estepa, 'El Reino de Castilla y el Imperio en tiempos del "Interregno"', in Julio Valdeón, Klaus Herbers and Karl Rudolf (eds.), España y el 'Sacro Imperio'. Procesos de cambios, influencias y acciones recíprocas en la época de la 'europeización' (siglos Xi-Xiii) (Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid, 2002), pp. 87-100.

[48] Run into Barbara Schlieben, Verspielte Macht. Politik und Wissen am Hof Alfons' X. (1252 – 1284) (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2009), esp. pp. 166-292 and 194-202.

[49] It is significant that the cope of the Toledan archbishop Sancho II of Aragón, still preserved in the sacristy of the cathedral, shows the German language imperial eagles together with the Aragonese confined and the castles and lions of Castile and León. See Nickson, Toledo Cathedral, pp. 124-125 and Fig. 65. Archbishops Sancho I and Sancho II were members of the royal family simply had relatively independent positions at court. See O'Callaghan, 'Alfonso X and the Castilian Church', p. 428. An epitome of Alfonso X as an emperor with the majestic eagle is found in ane of the windows of the cathedral of León: see Estepa Díez et al., Catedral de León, p. 282.

[fifty] Francisco J. Hernández, '2 Weddings and a Funeral: Alfonso'south Monuments in Burgos', Hispanic Research Periodical 13 (2012), pp. 405-31.

Download PDF

The 'Sumptuous Style': Richly Busy Gothic Churches in the Reign of Alfonso the LearnedDOI: x.33999/2019.46

Source: https://courtauld.ac.uk/research/research-resources/publications/courtauld-books-online/gothic-architecture-in-spain-invention-and-imitation/2-the-sumptuous-style-richly-decorated-gothic-churches-in-the-reign-of-alfonso-the-learned-henrik-karge/